By RAQUEL RUTLEDGE

Posted: Jan. 20, 2006

Pfc. Katherine Jashinski dresses in uniform every day, but instead of

drilling for war with fellow soldiers, she spends her time on an Army post

in Georgia sweeping floors, scrubbing bathrooms and wondering whether she's

headed for jail.

The 23-year-old soldier from Wautoma, a member of the Texas National Guard,

refuses to pick up a gun. She disobeyed orders to attend weapons training

and refused to deploy to Afghanistan with her unit, moves the military

considers criminal.

Jashinski does not want to go to Afghanistan, Iraq or anywhere with the

Army. She says she disagrees with war of any sort, could never kill anyone,

and wants out of her six-year contract.

"I thought about going to Canada, but I don't feel like I should have to

leave the country for something like this," Jashinski said. "I don't feel

like I should have to run from my government. I should face them instead."

Jashinski is among a growing number of military members seeking to shed

their uniforms and cut loose from their commitments to fight on behalf of

the United States. They're seeking all sorts of outs including medical,

psychological, pregnancy and dependency discharges, and more and more like

Jashinski are applying for conscientious objector status.

Some call them cowards, noting that nobody forced them to join. Others

champion their courage. As war rages in the Middle East, some troops who

volunteered for military service are sparking controversy by now espousing

peace amid a monolithic muscle machine dependent on soldiers following orders.

Disagreement over the numbers

Conscientious objectors constitute a minuscule number of the military's 1.4

million active-duty members, officials say.

"The numbers have gone up marginally," said Army spokeswoman Lt. Col.

Pamela Hart. "But we have a lot more individuals on active duty."

In all, 110 troops sought honorable discharges from the military through

conscientious objector applications in 2005, more than double the number in

2001, according to figures supplied by the service branches.

Those defending objectors say the numbers are much higher.

J.E. McNeil, executive director of the Center on Conscience & War, a

Washington D.C.-based non-profit that has supported the rights of

conscientious objectors since the 1940s, said her organization alone helped

nearly 100 troops file the complex paperwork in 2005.

"That's ridiculous," McNeil said of the military's figures. "The numbers

don't jibe. I know of at least another 20 groups that do what I do, plus

people do it on their own or with the help of local ministers."

McNeil said she hears from military members whose sergeants tear up their

paperwork and of many cases where the paperwork is repeatedly lost.

Military officials acknowledge that some applications may have been lost,

but they said they had not heard of any such cases, or of any where

commanders destroyed an application.

"We would take that very seriously," Hart said.

The Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors, a non-profit

organization that counsels service members on ways to get out of the

military, says calls to its GI Rights Hotline have soared in recent years,

to 32,000 in 2005 from 12,000 in 2000. Two to three calls a month come from

Wisconsin National Guard members, hotline counselors said.

Gaining objector status is difficult

Before refusing orders to report to weapons training, Jashinski applied for

discharge as a conscientious objector. Her request was denied. For the

military to approve a conscientious objector application, service members

must show they hold a "firm, fixed and sincere objection to participation

in war in any form or the bearing of arms," for deeply held moral,

religious or ethical beliefs.

It's a cumbersome task, considering that they willfully joined an

organization that has combat as one of its main missions.

Unlike the draft days of the Vietnam War, troops today must prove they came

to their beliefs after joining the military. Their reasons may not stem

from philosophical or political beliefs. They cannot agree with certain

wars and object to others, under the military's definition. And to

demonstrate their sincerity, aside from a lengthy application, troops

seeking discharges as conscientious objectors must interview with a

chaplain, military investigator, and a psychiatrist.

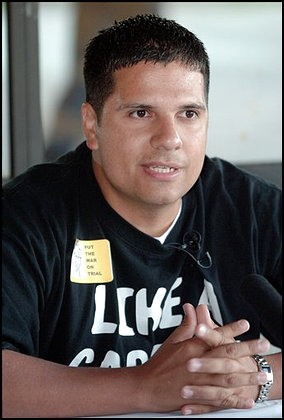

Petty Officer 2nd Class Mike Tonn from Fond du Lac served more than three

years in the Navy before requesting a conscientious objector discharge in

2004. Tonn was 18 when he joined in July of 2000 "as a way to get out of

Fond du Lac, Wisconsin," for the adventure and college money. It was

pre-9-11 and he never thought he'd go to war.

Tonn said he realized he couldn't carry out the Navy's mission after the

captain of the USS Lake Champlain asked him to give a speech to sailors on

Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday.

"He (King) pleaded to American soldiers they should get out of the war in

Vietnam and it clicked with me," Tonn said. "I believed in what Martin

Luther King said. . . . I realized I'm not going to walk down the street

and kill someone."

Tonn's request was approved about four months later and he received an

honorable discharge, but not before investigators tried to "trap" him with

aggressive and passion-provoking questions, he said.

Tonn sought advice from an anti-war group before applying and interviewing

and was prepared to answer the tough questions, he said.

Tonn said a few shipmates called him names but there was no serious

backlash from superiors or civilians once he returned to Wisconsin. He now

is an active member of Peace-Out and advises other troops on the

conscientious objector process. He is attending college in Portland, Ore.

Objectors face disapproval back home

Vietnam War veteran Frank Wilke said he fought for the rights of Tonn and

others to have freedoms like choosing to be a conscientious objector to

war, but he disapproves of people who choose such options.

"I defend their right to do that," said Wilke, who's active in the

Wisconsin chapter of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. "At the same time, I

also have the right not to associate with people who do that.

"When you do something like that, you're not only hurting your country, but

hurting your friends and family."

Jashinski knows about that. Her decision to seek a conscientious objector

discharge has strained her relationship with her family, she said.

"I really can't bring it up to my dad any longer," she said. "I feel like

we'll never agree. And some of the things he says make me pretty angry."

Cindy Jashinski, Katherine's aunt, said she and her husband disagreed with

Katherine's decision.

"We feel she committed to this. She enlisted. She should finish her time,"

Cindy Jashinski said.

Jashinski joined the Texas National Guard in 2002 after moving to Texas to

attend college. She was 19 and wanted to "experience as much as she could,"

and to help pay for college. She said she was raised Christian and believed

killing was wrong but that it was sometimes necessary.

"I was prepared to go to war," she said.

But her feelings and beliefs began to change over the next two years as she

watched from her TV and computer the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and as

she traveled the world and talked to citizens of other nations. She began

to read history and philosophy and began questioning the morality of all

wars, she said. By the time she received activation orders in April 2004

and was told she'd be going to Afghanistan, she said she had decided that

taking a human life was wrong, no matter what.

"One of the most important things a person can do is honor their word and

keep their honor that way," she said. "But I realized I'm going to have to

live with it for the rest of my life and that it's more important to follow

my conscience than to fulfill a contract I signed when I was 19 and didn't

know any better."

Jashinski filed a civil suit in federal court in San Antonio after her

conscientious objector application was denied. The outcome of that case is

pending. Meanwhile Jashinski has been demoted from specialist to private

first class. She is confined to a 2-acre compound on Fort Benning while she

awaits a court martial - similar to a civilian court trial - from the

military. She likely faces up to one year in prison if found guilty of

"missing movement" with her unit.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: